The history and evolution of Montbell sleeping bags

2016/11/24

For overnight hikes or long trails, a good night's sleeping is extremely important. If fatigue carries over to the next day due to a lack of sleep, it can contribute to an inability to concentrate, which could possibly lead to a stumble and maybe even injury. "Warmth" especially is a crucial element that can determine whether or not you get a good night's sleep. Montbell's president Fumiaki Masaki will take us through a history of sleeping bags in Japan, the transitions in insulating materials, design and functionality, and the ever important concept of "warmth".

Is "warmth" solely determined by insulation weight?

Until about 40 years ago, almost all insulation for sleeping bags was made with synthetic fibers. At the time, in order to increase heat retention it was necessary to increase the density of the insulation, which made the bag heavier. This is why it was thought that warmth was equal to the amount and density of insulation. The warmer the sleeping bag the bulkier it was, and the heavier the bag the more expensive.

At the time, there were down sleeping bags in circulation, which were half the weight and provided the same amount of warmth, but these items were used by a select group of experts who would go on expeditions overseas, and these bags were far beyond the reach of the everyday climber or hiker. In those days, sleeping bags from manufacturers in Europe, were extremely expensive and usually cost the average college graduate about 2 or 3 months worth of wages.

Although, inexpensive down bags were available. In the 1960s, due to the Korean War, a large quantity of discarded bags from the U.S. Army would circulate in Japan, and local entrepreneurs started making their own versions, copying the structure and using synthetic fibers. In America and Europe these bags were known as "mummy bags", but in Japan they were called "human-shaped" because they were different from the envelope style bags and fit the human form. The very first sleeping bag I used was such a "human-shaped", and I remember that it was made without wasting materials and it was a really great bag.

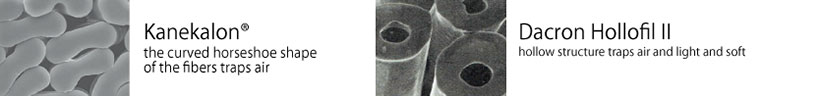

At the time, synthetic insulations were made of nylon, Tetoron (polyester), and acrylic, but for sleeping bags, an acrylic fiber called Kanekalon was primarily used. Though it doesn't quite have the heat retaining properties of today's hollow fibers, the curved horse-shoe shaped fibers of Kanekalon would hold dead air, and therefore be warmer than other synthetic fibers.

The transition from "Big and Warm" to "Small and Warm"

With Japanese sleeping bags sticking to the standard that "bigger was warmer", a major turning point came in 1974, when the American company DuPont came out with a new sleeping bag insulation made from polyester fibers called Dacron Hollofil II. By producing these fibers in a hollow, macaroni-shaped structure, they could hold a significantly larger amount of dead air to retain warmth, making them fluffy and soft, lightweight and water resistant. Best of all was its amazing ability to recover loft, just like down, it could be compressed very small but would return to its normal size.

At the time, I was working on research and development for sleeping bags, and I immediately set about using this Dacron Hollofil II to develop products. Because this insulation had such high lofting properties, I wanted to make the sleeping bag's fabric as thin and lightweight as possible. I decided to use a slim computer ribbon tape-like material that was at the time the thinnest in the world, and produced only in Japan. Where we had once used 70-denier fabric, this new, thinner 40-denier fabric, made an incredibly lightweight sleeping bag.

In 1976, after approximately 2 years of development, we released a new sleeping bag with the marketing message "compact, lightweight, and warm". But at first we struggled to gain acceptance. When we took it around to local wholesalers in the southern region of Japan, they told us, "This little bag is the same price as a bigger bag? No way." So next we decided to try selling it in Tokyo. Climbers in Tokyo must have been tired of dealing with big sleeping bags, because they were instantly attracted to the compact size of the bags, because they could fit into the bottoms of their backpacks. Sales were sensational. Although we had only recently established ourselves in 1975, Montbell's reputation suddenly exploded.

This new down-like synthetic fiber attracted a great deal of attention, and 2 to 3 years later other fiber manufacturers would follow suit. Within a few years, the Dacron Hollofil II sleeping bag supplanted the traditional sleeping bag for climbers. The mainstream thinking used to be "big and heavy", but it was now shifting towards "lightweight and compact". I believe that this was the defining moment of change in the history of sleeping bags.

The Clo Value : a guide to warmth

If you go to an outdoor shop today to buy a sleeping bag, you'll find sleeping bags are advertised with temperature ratings such as, "You can sleep comfortably with this sleeping bag down to minus X degrees." But until about 30 years ago, there were only 3 choices for a sleeping bag: summer, 3-season or winter. This made the standards for selecting a bag extremely vague. Climbers and hikers would ask, "Is a summer bag appropriate for high altitudes in summer?" or "If I'm going to be hiking low altitudes in winter, will I really need a winter bag?" Decision making came down to your own personal outdoor experiences and intuition.

The reason these vague categories became the ratings of today was a result of the "clo value." This value represents insulation as a numerical unit, and is based on data collected by the U.S. Army from 20,000 soldiers who were measured under all sorts of conditions. Because now we were able to understand the insulation level of a sleeping bag in specific numerical values, the standards were no longer vague, and it enabled people to choose the best bag depending on their destination and weather conditions.

Today, the EN13537 European standard has come into use, which standardizes temperature ratings for each sex based on various environmental conditions. But still, "warmth" is subjective and varies from person to person, and is not an absolute value. Although a chart might designate a certain value as appropriate, a person might experience that value as cold or even hot. We should keep in mind that these values should ultimately be used as a "guideline" or "reference point". According to one theory, the standard temperature which a person feels comfortable has apparently risen 3℃ compared to 30 years ago. It appears that valuation standards of temperature may continue to change with the passage of time.

Clo Value

1 Clo is the equivalent of insulation a person at rest needs to maintain a skin temperature of 33 degrees Celsius in a room with 50% or less humidity, 21 degrees Celsius and wind speed of 5cm/second. For example, at 0 degrees Celsius, 4.5 Clo is necessary to stay comfortable (i.e. comfort rating) and 3.4 Clo is enough to get by (i.e. limit rating). This is how the Clo was used to scientifically study and describe the relationship between warmth and quality of sleep. (ASTM D1518 Standard)EN (European Standard) 13537

European Standards are standards and specifications for products used throughout the European Union. EN 13537 is the standard that defines how temperature ratings for sleeping bags are calculated. Before this standard it was common for each manufacturer to have their own system for rating sleeping bags.EN135371 Testing Method

A thermal manikin is dressed in long underwear and placed inside a sleeping bag lying down. A heating element within the manikin is used to heat the manikin to body temperature and sensors record how much power is used to maintain body temperature. These readings are then used to calculate temperature ratings.

EN 13537 Temperature Ratings

Comfort Limit: the temperature at which a standard woman can expect to sleep comfortably in a relaxed position.Lower Limit: the temperature at which a standard man can sleep for eight hours in a curled position without waking.

Extreme Limit: the minimum temperature at which a standard woman can remain for six hours without risk of death from hypothermia (though frostbite is still possible).

The Stretch System: staying warm and a good night's sleep

Everyone has had the experience of a cold night on a mountain or a hike, and the cold is making it real hard to get to sleep and you might tug at the hem of your sleeping bag, to try to get just a little bit warmer. Just as a mummy bag is warmer than an envelope-style bag, the closer the insulation in a sleeping bag is to the body, the better it retains heat. However, if the bag is too tight, it can be constrictive and conversely deprive one of a good night's sleep. So how is it we can utilize insulation in the most efficient way possible? The hint to that answer lies in all those cold nights spent tugging at the hem of a sleeping bag. This hint lead to the idea of stretchable sleeping bags.

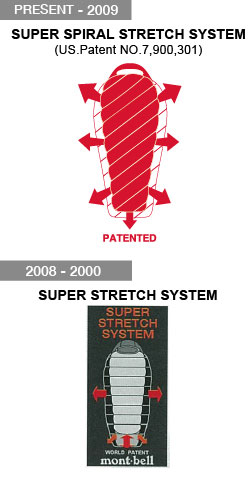

The inside of a sleeping bag is constructed to prevent the insulation from gathering to one side, or separating, through divisions created by stitching and non-woven fabrics. In 1988, we added elastic to these stitched areas to create a stretch system. The elasticity would add a relaxed, comfortable experience while providing an appropriately close fit. After acquiring a patent for this idea, we granted licenses to several manufacturers, such as Sierra Designs and Mountain Equipment, and now stretchable properties in sleeping bags are familiar to people throughout the world. Although that original patent has expired, we have continued to innovate and make revisions to the design, such as positioning the stretchable threads diagonally to eliminate tightness and improve fit, so our sleeping bags can provide an even better night’s sleep.

Some final words and advice on sleeping bags

Everyone has had the experience of feeling too cold in a sleeping bag and layering clothing to get through the night. If you layer your clothing, naturally it will become tighter and more difficult to sleep, but it's still better than losing sleep because of the cold. During these times, you want to make sure that you don't wear rain gear or other types of clothing which can become stuffy. Although most types of rainwear are breathable to release moisture that builds up inside the rainwear, rainwear does make it more difficult for perspiration to escape from the body, making you feel sticky and sweaty. Instead of layering clothing, back in the day we would fill an aluminum thermos with hot water to use as a hot water bottle, but now there are more convenient products such as disposable heating pads, so you may want to consider packing some of those on your next trip.

Also, I think that it can be a good idea to combine 2 sleeping bags together. For example, if you insert a summer bag inside of a 3 season bag, you should be able to use this set up for winter. But in winter alpine conditions, there are some downsides, such as having to open and close 2 sets of zippers, and dealing with the slight increase in weight. I feel that the extra weight isn't that noticeable. I feel this sleep system is not only economical, but also versatile for use throughout the year. I heartily recommend it.

Sleeping pads : a necessary accessory

The warmth in a sleeping bag is derived from the loft in the insulation. Conversely, no matter how high the heat retaining properties of the insulating material, without lofting there is no warmth. When sleeping, the insulation in contact with the back (the side placed to the ground) is compressed due to the body's weight, and in especially cold climates the ground acts as a sink to suck warmth from the body. This is why it is necessary to have a sleeping pad to insulate the body from the ground. The pad also has the added benefit of cushioning and helping improve sleeping conditions.

Sleeping pads are largely divided into three types; air pads, which are pumped with air, foam pads, made of a spongy material, and in between these categories, self inflating pads. An air pad has the benefit of being compact and stores easily, but in snowy conditions where the ground is cold, the heat exchange which occurs through air convection can deprive the body of its heat, in which case you should select a foam or self inflating pad. The optimal size for a pad is one that covers the length of your body, but if you want to lighten your load, you can stick your feet in or on top of your backpack, or use your clothes or jacket as a pillow.

Questions from readers

Q: During winter, there's water on the outside of my sleeping bag when I wake up. Is there anything I can do to prevent this?

(Answer) During winter time, the moisture from your breath condenses due to the difference in temperature, and adheres as frost around the opening of your sleeping bag. And when this fabric comes into contact with your face, you will feel the cold and wet, and it’s uncomfortable. You can minimize this by wrapping a muffler or scarf around your neck and face. However, you can also burrow deep inside your sleeping bag, keeping your mouth and nose away from the opening. By keeping the warm air from your mouth away from the opening, you can mitigate the condensation, and the added benefit of your breathing will help keep you warm inside your sleeping bag.

Q: My feet are always cold. Do you have any advice?

(Answer)If your sleeping bag is long and has extra space, you can bunch up the bottom of the bag, increasing the density of insulation at your feet, and increasing heat retention. Another alternative is wrapping a sweater or down jacket around your feet. If your socks get wet, don’t try to dry them out by wearing them. Instead, change into dry socks, or warm your feet with your hands. Disposable heating pads are also convenient.

PROFILE

Fumiaki Masaki was born in Osaka Prefecture, 1952. He is the Advising Director of the Board at Montbell. In 1972, he went on an expedition in Europe and climbed the north face of the Grandes Jorasses and was the first Japanese climber to climb the western face of the Aiguille de Dru. In 1975, long time climbing partner and current CEO of Montbell, Isamu Tatsuno asked Masaki to go into business with him and the two formed Montbell. Over the years Masaki would be involved in product research and development, production and sales. His area of expertise is materials, particularly fabric and fibers.

© mont-bell Co.,Ltd. All Rights Reserved.